Meet an Educator is a monthly series by Early Bird, where we feature the work of educators across India who are actively spreading the joy of birds and nature. This month’s featured educator is Anurag Karekar, a monsoon-migrating naturalist from Mumbai, runs nature education and ecotourism programs through his company, Naturalist Explorers.

Do tell us about yourself, where you are from, and your work

Hi, I’m Anurag Karekar—a monsoon-migrating naturalist! I work as an Ecotourism Curator at The Habitat Institute in the Andaman Islands for eight months of the year, and return to Mumbai during the monsoon to run nature education and ecotourism programs through my company, Naturalist Explorers. I was born and raised in Mumbai, with ancestral roots in Goa. My earliest memories of nature come from spending time outdoors with my father, a humble nature enthusiast. While other kids were glued to WWE, I was watching Animal Planet and Discovery. By the end of Class 10, I was sure I wanted to work with wildlife—though I thought the only way was to become a rich doctor or engineer and buy my own forest (Nat Geo’s African models clearly had an influence!). How I stumbled into zoology and wildlife science is a story best told on a walk through nature.

What excites you about the natural world?

During my Bachelor’s degree, I was surrounded by passionate seniors who picked their niches—birdwatchers chasing sightings, herp enthusiasts handling snakes, and butterfly lovers mesmerized by colors. But I found myself drawn to something different: ecology, ethology, and evolution. I was fascinated by how all these creatures coexisted, interacted, and adapted. Why did a species prefer one prey over another? How did a minute morphological trait give it an advantage? Why did it appear only in specific seasons or habitats? These questions captured my imagination.

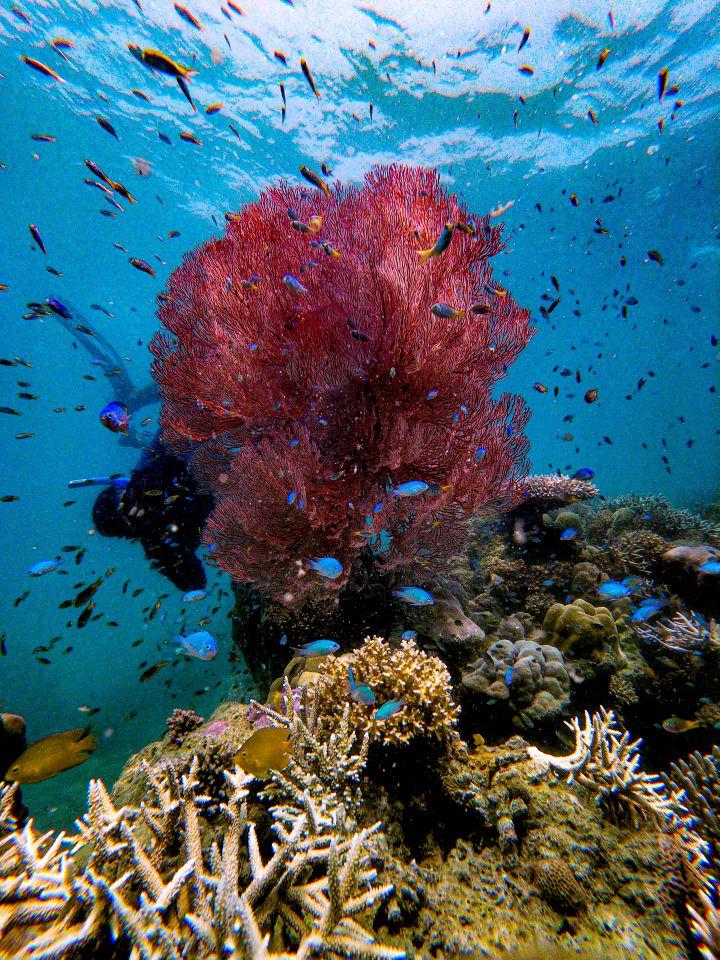

Later, I was introduced to marine biodiversity—which, to me, was like opening a time capsule. Every tidepool, coral, or reef was an evolutionary puzzle, full of bizarre adaptations, ancient behaviours, and species that blurred the line between the past and present. The natural world is a live theatre of adaptation, interdependence, and wonder. What excites me most is observing this ongoing drama—whether it’s a crab mimicking coral, a bird timing its migration perfectly with the monsoon, or a wasp paralyzing prey with surgical precision. Nature constantly challenges my understanding, humbles me, and deepens my curiosity.

When and how did you get interested in bird/nature education?

Honestly, I didn’t hold nature education in high regard in the early years of my career. I saw it as a way to earn some pocket money on the side while doing “real” wildlife work. That perception changed entirely because of one place: the Vasai saltpans.

The saltpans were an ecological paradise—teeming with ducks, storks, waders, grassland birds, raptors, and more. But this rich habitat wasn’t protected, and very few people knew of its existence. In fact, many birders and wildlife photographers who did know about it treated it like a secret, fearing publicity would lead to damage. Unfortunately, because it was so hidden and unknown, people never got the chance to understand its true ecological value. By the time we realized how vulnerable it was, it was already too late.

Seeing signs of land-use change and construction, my team and I—part of a youth-led conservation group—organized public trails to raise awareness. The response was incredible: students, professors, and citizens were amazed by the biodiversity. But it triggered backlash. I was accused of “exposing” a secret. Soon, local land mafias began threatening visitors. Due to the violent and unsafe atmosphere, people stopped coming, and eventually, the area was lost to development.

That incident hit me hard. I contrasted it with places like Bhandup Pumping Station or Aarey, where people had regular access and deep emotional connections—those places were fought for and, to an extent, protected. That’s when I understood: conservation can only happen when people feel ownership, and that comes from direct experience. Nature education isn’t a side hustle—it’s the foundation of grassroots conservation. Since then, I’ve devoted myself to it fully.

What do you hope to achieve through your education work?

My goals through nature education shift based on who I’m working with. When I engage with travellers and guests, I aim to make ecotourism and experience-based travel more mainstream. I want them to understand how conscious and responsible travel can generate financial incentives to preserve ecosystems and cultural heritage. When people value local biodiversity and traditions, they create a demand that discourages exploitation and supports conservation-linked livelihoods.

With local communities, my goal is to nurture a sense of pride, respect, and value for their natural surroundings, cultural roots, and simple, sustainable ways of life. Unfortunately, western influence has made materialism and hyper-consumerism aspirational. I want to challenge that narrative, to show that dignity lies in a harmonious, minimalist lifestyle deeply rooted in nature.

My third focus is on cultivating coexistence—helping people understand the wildlife around them and how to be better neighbours. Whether it’s learning to live alongside urban monkeys, birds, or snakes, or ensuring we leave space for wild species in our cities and villages, coexistence is key. Through my work, I hope to make people more aware, respectful, and empathetic toward both the visible and invisible creatures that share our spaces.

Why do you believe it is important for children to learn about birds or connect with nature?

Children are malleable, curious, and open to wonder—nature leaves a lasting impression at that age. I’m sure every reader of this blog, and many fellow educators, had some early exposure to nature—maybe through village visits, zoo trips, treks, or just playing outdoors. That spark shapes our empathy, imagination, and understanding of life beyond ourselves.

Children raised in cities with no nature exposure often grow up fearing butterflies, expecting sterile, “nature-proof” resorts in national parks, and feeling indifferent when trees are cut or rivers are polluted. By adulthood, our minds are often like brimming cups—hard to fill with new ideas. But children? They’re still empty, open, and eager.

Kids also have unmatched power to drive change. Their intentions are pure; they aren’t yet consumed by jobs, money, or survival. They’re willing to fight for love, life, and the planet—because they have nothing to lose. Adults often hesitate. But children can become powerful ambassadors for nature. I truly believe that many of the most passionate environmentalists started with a positive connection to nature early in life—and it’s our job to spark that connection.

What tools or resources have helped you in teaching about birds? Can you describe an approach that has worked exceptionally well for you?

In the early days of our foundation, we used simple graphic flex boards to explain complex ecological concepts during sessions called “Naturalist Talks.” Visual tools helped break down topics like food chains, habitat loss, and climate change into accessible stories.

Photography has also been a powerful tool—but not just professional photography. We started promoting jugaad methods like using binoculars with phone cameras to capture birds or macro lenses to reveal insect details. Teaching guests how to use their mobile cameras to observe nature closely made the experience hands-on and memorable.

Another game-changer has been citizen science apps like iNaturalist and Merlin. We encourage our guests to upload their sightings, which gives them a sense of contribution to real science. It also helps build their ID skills. Soon, they begin to explore and search for species on their own—learning becomes a game.

Merlin, especially with its bird call feature, adds a new dimension. We play back calls, try to mimic them, and suddenly birdwatching becomes not just about sight, but sound too. It creates moments of laughter, awe, and learning.

Ultimately, any tool that makes people more observant and curious—whether it’s a field guide, a mobile app, or their own camera—becomes a tool for transformation.

Have you encountered a significant challenge as a bird/nature educator, how did you overcome it?

One of the biggest challenges I face is dealing with people’s emotional expectations from me as a nature educator—especially the assumption that I will always intervene to “save” animals.

Once, a parent told me that their child had found a kitten and brought it home. They expected me to find someone to adopt it. I gently asked them to return it to the exact place it was found. The parent was furious. I explained that the kitten may have a mother who had simply left to hunt. Without that knowledge, picking up a street kitten is often equivalent to kidnapping. Only when I asked them to imagine a tiger cub in the same situation did they understand my point.

Another case involved a society member who fed stray cats to the extent that they became obese and lost all instinct to hunt. Mice and cats were eating side by side! In such cases, people mean well, but by creating dependency, they disrupt natural behavior and ecological roles. Future generations of those animals may never learn survival skills.

These conversations are emotionally charged. You have to approach them slowly, with empathy, and acknowledge the person’s good intentions. Sometimes, even then, you must be ready to step back—because challenging deep-seated beliefs takes time. But I’ve learned that respectful, patient dialogue—rather than confrontation—is the key to shifting mindsets.

Do share any memorable moment or experience you have had in teaching kids about birds/nature. Can you recall any insightful instance that shaped your perspective?

One of my favourite teaching moments happened on a marine trail. I noticed the burrow of a snapping shrimp and began explaining its fascinating partnership with the goby fish—how the goby stands guard while the shrimp digs, both living in symbiotic harmony. Just as I finished explaining, the goby popped out to keep watch, and the shrimp followed, burrowing exactly as I had described. The timing was magical—and the kids were in awe.

This kind of serendipity has happened often. I might explain a bird’s mating dance or an insect’s camouflage technique, and then nature puts on a live demonstration. The kids light up with joy and disbelief, and I feel like a magician whose trick just came true—except the magician here is nature itself.

Moments like these deepen my own observation skills and understanding of animal behaviour. They also reinforce the idea that field learning—seeing, hearing, and experiencing nature live—is far more impactful than any textbook or screen. These interactions create unforgettable memories for kids and often become their first step into a lifelong bond with the natural world.

Have you noticed any changes in your learners after they received exposure to birds and nature-based learning? If yes, what are they? If not, why do you think that is?

Yes—every time. Exposure to nature leaves a lasting impression, especially on children. When they see a creature they’ve never noticed before, it activates their sense of wonder. If it’s a species they’ve seen earlier in books or cartoons, there’s a strong memory recall coupled with a dopamine hit. This builds a positive emotional connection.

I’ve seen children who were initially scared of insects slowly grow curious. Others start asking deep, insightful questions. Some even begin telling their own nature stories—recalling past experiences with frogs, birds, or butterflies. That’s when you know something has clicked.

This exposure also makes them more receptive to conservation messages. They begin to care, empathize, and think critically. A child who once squashed bugs may now stop others from doing so. These may seem like small changes, but they are the seeds of future environmental consciousness.

What message would you have for your fellow educators, or somebody starting out in their nature education journey?

Respect this work—it’s a calling, not just a side hustle. As nature educators, we hold the power to shape future conservationists, scientists, activists, and storytellers. But to do justice to that, we must strive to become better communicators and deepen our understanding of the natural world.

Go beyond textbook facts. Observe. Question. Explore. The more you immerse yourself in nature, the more it teaches you. You don’t need to know everything—but you do need to stay curious and be honest about your learning journey.

Your enthusiasm, humility, and integrity will leave lasting impressions. Don’t underestimate your influence. A single nature walk, one story, or one answered question might be the moment a child decides to dedicate their life to the environment. That’s how powerful your role can be. Treat it with the respect it deserves.