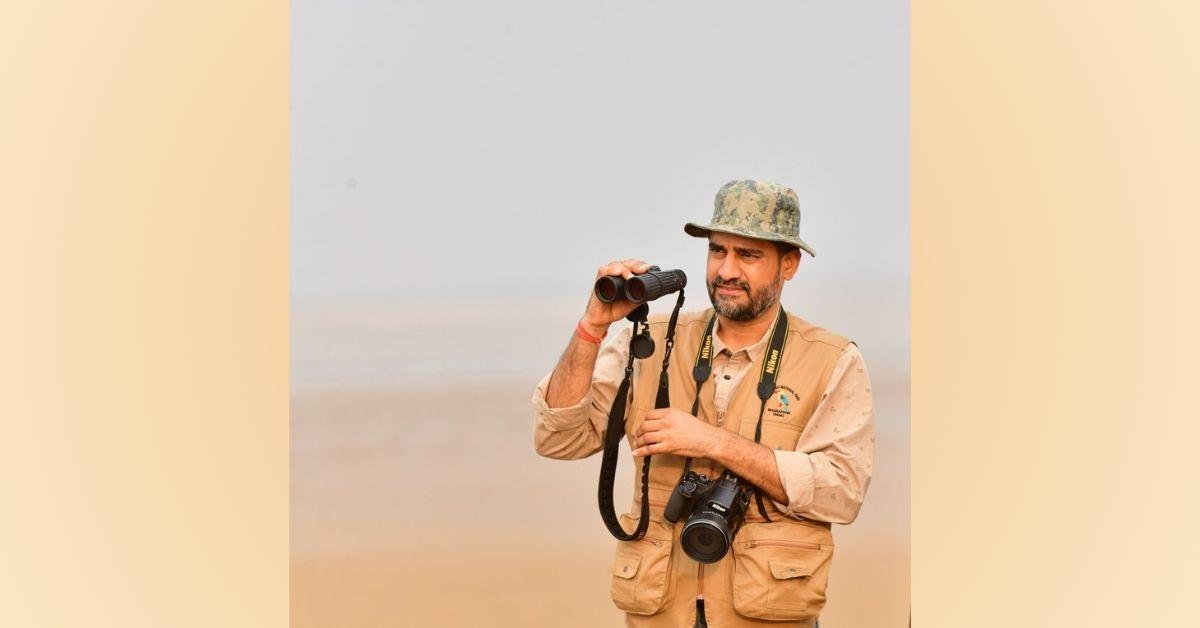

Meet an Educator is a monthly series by Early Bird, where we feature the work of educators across India who are actively spreading the joy of birds and nature. This month’s featured educator is Sumit Dookia, a nature educator from western Rajasthan. He leads landscape-level awareness campaigns to conserve threatened species.

Do tell us about yourself, where you are from, and your work.

I am a native of a small town in western Rajasthan, and I completed my doctoral work (PhD) in the ecology of wild ungulates from the same region. Since childhood, I have been interested in natural history, with a quest to explore more about the surrounding biodiversity. I learned a lot from local community-based narratives shared by elders in my family and under the guidance of my father, a zoologist and college professor. I also accumulated biodiversity-related phrases and stories from my grandparents and cousins during our annual rendezvous trips in the winter and summer breaks.

I started identifying and differentiating birds at an early age, thanks to my father lending me a pair of binoculars. I took it as a regular activity during my doctoral fieldwork. I used the same binoculars to jot down the behaviour of focal animals while simultaneously listing birds. As a university faculty member specializing in animal ecology and wildlife biology, I have ample opportunity to bring all my experiences and learning into teaching and training the young students, just as I learned as a small curious kid.

What excites you about the natural world?

I am a professional who earns his bread and butter by pursuing what started as a part-time hobby, eventually transitioning into a full-time role as a teacher, trainer, and mentor. I believe that birding is a hobby that can truly make you appreciate nature’s creations in the form of birds. Their social behaviours, intricate songs, migratory patterns, and breeding displays all showcase the beauty and complexity of the natural world.

Though I’ve been birding for many years, there’s one particular episode I’d like to share that took me quite some time to unravel. During the evenings, I used to go for walks with three friends, escaping the chaos of the city to explore the wilderness on the outskirts. One fine evening in the early 90s, as twilight descended, we would always hear a loud bird call, but we struggled to identify the species without actually spotting the bird.

This quest led me into a whole new world of bird songs and calls. It wasn’t until the year 2000, when I stumbled upon the Wildlife Institute of India‘s library and came across a tape cassette titled “Call of Indian Birds,” that I finally discovered the identity of the bird behind that distinctive call. It turned out to be the Indian Stone-curlew or Indian Thick-knee! A bird that remains mostly silent during the day but becomes quite vocal during the breeding season at dusk.

When and how did you get interested in bird/nature education?

During my doctoral work, I regularly visited the field site for three years with binoculars, observing a single species to study their behaviour. To break the monotony, I explored the diverse avian life in the area, which became my hobby. I delved into bird watching and studying their calls, venturing into different habitats across western, northern, and central India for field projects.

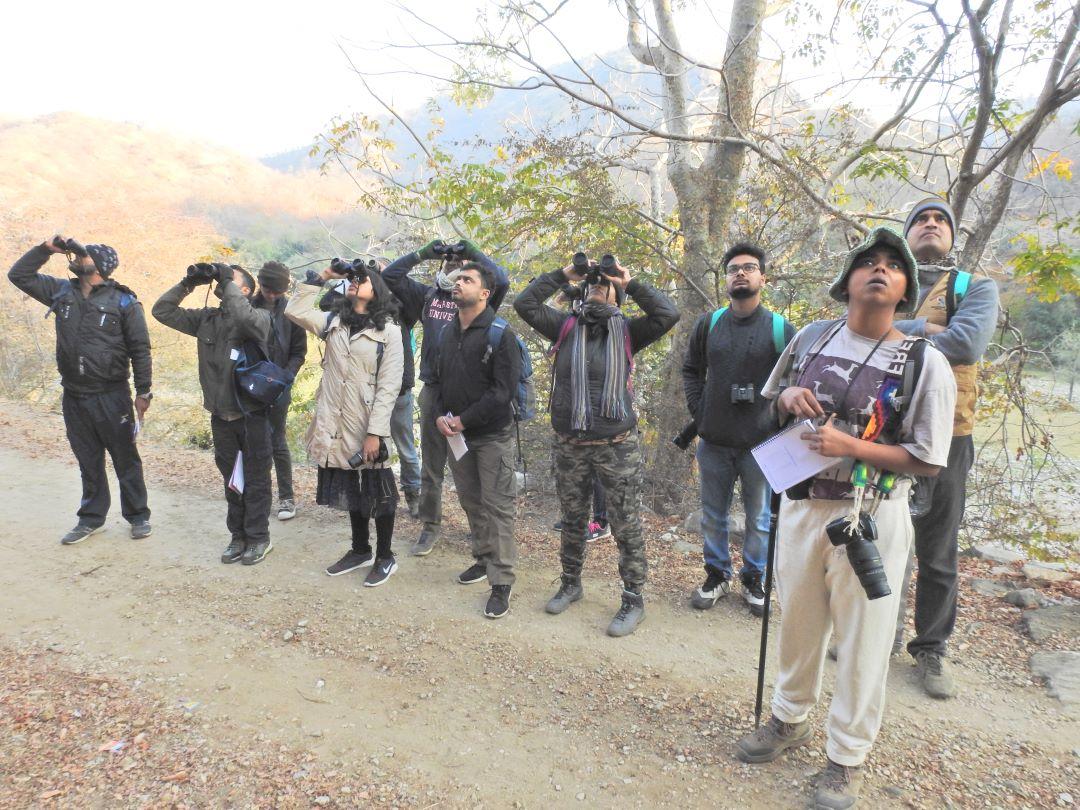

Before the era of the internet, through many friends and sources, I started making a collection of bird calls, which nowadays has become much easier to confirm with just one click on Xeno-canto or the Merlin app. I often took colleagues, friends, or students on bird walks, offering detailed explanations to enhance their experience. They quickly developed an interest as I shared anecdotes and insights about the birds, making the sightings more memorable.

What do you hope to achieve through your education work?

In my view, sharing knowledge expands one’s own knowledge base. During my doctoral field work, I often had friends, juniors, or village youths accompany me, fostering interest in birding and wildlife among them. Since 2006, I’ve conducted landscape-level awareness campaigns to conserve threatened species, forming small groups with similar interests for school workshops.

The Great Indian Bustard has been a key focus of my work in western Rajasthan. I aim to empower local youth to lead in conserving threatened species, especially the Great Indian Bustard. Many trained by my team now freelance as birding guides in Jaisalmer, aligning their passion with their profession and securing their livelihoods.

This dual commitment to passion and profession motivates them to safeguard the Great Indian Bustard, monitoring birds beyond protected areas and joining anti-poaching efforts with the ERDS Foundation, a local NGO I’m associated with in an honorary capacity.

Why do you believe it is important for children to learn about birds or connect with nature?

We all have an innate connection with nature, and from a very early stage, the omnipresence of House Sparrows, Red-vented Bulbuls, Indian Peafowls, and Rock Pigeons around our houses becomes the first birds that we see. Birds are also associated with many folklore and bedtime stories in rural areas, and children have a natural quest to know more about such aspects.

Whenever we conduct awareness workshops and sessions, within a few minutes, children start getting involved in many discussions about them, because we discuss almost everything in their own dialect and language. Through such enriching and interactive sessions on native biodiversity and birds, we try to create more curiosity among these young minds and then allow them to start asking questions.

In my own experience, I can certainly say that if we are able to sensitize children about the role of birds in the surrounding ecosystem, the threats they face, and a few suggestions for them to work on this line, we can create very good birders in them.

What tools or resources have helped you in teaching about birds? Can you describe an approach that has worked exceptionally well for you?

In the present time, resources are plentiful, but customized and site-specific teaching aid resources are still lacking. When I began conducting awareness workshops, I used to create brochures, posters, flex prints, as well as PowerPoint presentations, and sometimes even carried LCD projectors into the field. Visual materials have a greater impact than written books or booklets.

I honed my skills in this area by volunteering for numerous landscape-level awareness campaigns with Dr. A. R. Rahmani (the then Director of BNHS) from 1999 to 2004. This experience provided valuable insights into the expectations of children from us as educators. We also distributed postcards among school children for them to write back with their queries.

Nowadays, the landscape has changed entirely, and I’ve incorporated a few more types of resource materials such as short clips featuring target animals/birds, as moving or video clips have a greater impact than still photos. Thanks to the internet and platforms like YouTube, such resources are readily available. My team and I also make an effort to explain everything in the local language, and we simplify concepts like the food chain and food web using examples from native biodiversity to make them easier for children to understand.

Recently, we’ve developed 2-3 resource materials on local biodiversity and a children’s storybook on the Great Indian Bustard. We are also in the process of designing a few more customized materials as part of our long-term strategy to establish a comprehensive conservation education program on local biodiversity, with the Great Indian Bustard as the keystone species for western Rajasthan.

Have you encountered a significant challenge as a bird/nature educator, how did you overcome it?

The biggest challenge is that our school curriculums still lack anything on native biodiversity. Even examples of flora and fauna are drawn from non-native and exotic species. We need to replace these with examples from our local biodiversity to better explain life forms and the environment. I always try to incorporate as many local biodiversity examples as possible into discussions with my students. This approach helps them connect more easily and understand the concepts better.

Do share any memorable moment or experience you have had in teaching kids about birds/nature. Can you recall any insightful instance that shaped your perspective?

In any area, whether it’s nearby or far away, there should be at least 20-25 species of birds. However, many kids and even adults only know about 2-3 common birds like pigeons or crows. When I give them a bird guidebook and ask them to spot the bird they’re talking about, the look of surprise on their faces is priceless. They realize that even crows have many different species.

To add even more wonder to their experience, I often suggest they try looking at birds through binoculars. The experience of spotting a bird through binoculars is mesmerizing for them. They’re amazed by the rainbow of colors they can see in the seemingly plain black wings of a crow when it’s illuminated by direct sunlight.

Have you noticed any changes in your learners after they received exposure to birds and nature-based learning? If yes, what are they? If not, why do you think that is?

The basic change lies in their perspective on seeing the birds and their increased interest in the natural history of such birds. Since almost all birding sessions happen in open areas, the learners are able to spot birds easily and also pay more attention to the approaching calls from nearby bushes. Birding takes them away from the chaotic daily routine, giving them a refreshing feeling even after walking many kilometres and spending hours in the open sun. This occurs because they seek a natural connection with the surrounding biodiversity.

What message would you have for your fellow educators, or somebody starting out in their nature education journey?

My message to everyone is that it’s a long journey, and we need to continuously incorporate more local stories into our educational materials. With the use of smartphones, we can quickly confirm calls and identify birds more accurately using high-resolution digital cameras. However, without adding storytelling to the session, the whole exercise remains incomplete. A skilled narrator can turn even a dull session into a fun one, making the journey more enjoyable for both learners and educators.

dr.sumit ..happy to know about your journey…I’m also a bird lover.. especially I HV a special love for house sparrow.. initially there were too many sparrow used to visit iny balcony but with the period of time it has drastically decreased nd left with only 1 last couple..kindly help me out to save this precious friend of human being from such heat nd other factors related to their demise