Meet an Educator is a monthly series by Early Bird, where we feature the work of educators across India who are actively spreading the joy of birds and nature. This month’s featured educator is Anand Pendharkar, a wildlife biologist and nature educator based in Mumbai, whose work focuses on imbibing among the principles of conservation, through observation, documentation, ecological restoration, climate action, and sustainability.

Do tell us about yourself, where you are from, and your work

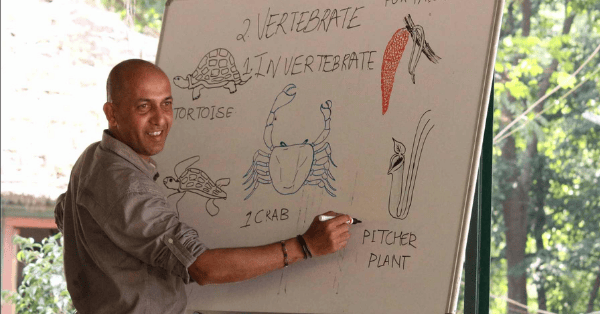

Trained as a Wildlife Biologist, graduating from the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) in 1993, my peers often peg my three-decade-long meandering career as that of a Nature Educator and Interpreter. However, I have consciously diversified and worn multiple hats to work with elan at the crossroads of conservation, spanning ecological research, advocacy, activism, outreach, mentoring, social entrepreneurship, ecotourism, and environmental consulting. Running the Mumbai-based umbrella organisation SPROUTS, the common thread between all these diverse careers is Nature education and knowledge creation. Engaging individuals, families, school and college students, (Eco-Leadership) Interns, via corporate and public engagements, camps, treks and tours, nature trails, camps, interactive lectures, co-operative learning, thematic workshops, and skill-development sessions or through the stringent boundaries of the various academic curricula that I have designed and teach, I attempt to imbibe among my participants (clients), the principles of conservation, through observation, documentation, ecological restoration, climate action, and sustainability.

What excites you about the natural world?

I’m not a species-oriented person and get excited by entire ecosystems, viz. the Himalaya, Trans-Himalaya, the deserts, plateaus, hill ranges, evergreen/deciduous forests, grasslands, savannas, mangroves, coastlines and islands, and even rural and urban regions of India. There is immense diversity in the natural world to provide inspiration, excitement and engagement, besides employment to the entire eight billion and more human beings, as it is doing to the remaining species of plants, animals, fungi and protists, on this planet. Whether one is thinking about food, colours, fashion, artistry, technology, medicines, behaviours, interactions, sustainability, evolution, infrastructure, music or sports, it’s all there, in infinite measure. There are several common and rare phenomena, life history strategies and/or behaviours of creatures, such as migration, symbiosis, polymorphism, camouflage, co-evolution, bioluminescence, superorganisms, murmurations, Arribada, synchronised (mass) flowering, and delayed implantation, to mention a few, which are engaging, amazing and worth observing for me, as a life-long learner. But, it is even more exciting as an International Educator to share the amazement of these and develop a scientific rigour among the teachers that I train, as also with the children, youth and adults, who participate in my workshops, certificate courses and outdoor programmes.

When and how did you get interested in bird/nature education?

As a toddler, I ran behind sparrows visiting our 2nd-floor Bombay apartment to feed on drying rice. During school vacations, our family visited my native place, Devrukh, which is a Nature haven, full of birds, butterflies, and plants, near the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve (Maharashtra), in the Northern Western Ghats. At that age, I wasn’t specifically inclined towards any wildlife taxa, but an ardent outdoor enthusiast, enjoying trekking, camping, and travelling across India, to explore fields, hills, forests and streams. It was during my 10th standard vacation that my parents sent me to a Nature-Adventure Camp in the outskirts of Pune (Bavdhan), Maharashtra. Kiran Purandare, the superlative Nature educator, enamoured me with his bird call mimicry skills and catapulted me into a lifelong bird watcher. This craze for birds coalesced permanently while participating in my college Nature Club activities. And in no time, I knew that this was my life’s calling.

What do you hope to achieve through your education work?

Through my educational initiatives, I aim to cultivate an enduring connection between individuals and their natural environment. My objective is to nurture ecologically-conscious citizens who deeply appreciate nature and recognise their responsibilities towards its conservation. I engage learners across the socio-economic and age spectrum, from pre-schoolers to doctoral fellows (including homeschoolers), teachers, parents and even corporate groups, through outdoor and experiential pedagogies.

Through my yearlong Eco-Leadership Internship Programme, I foster critical thinking, ethics, environmental empathy, and collaborative problem-solving skills among emerging socio-ecological leaders. These experiences are designed to leverage an individual’s ‘Circle of Influence’, to effect lifestyle changes and to repair, restore and rejuvenate ecological landscapes in urban, rural, tribal, and wilderness regions. Over the last three decades, I’ve created a cadre of over fifty well-trained second and third-generation conservation practitioners who understand the ecosystem services provided by biodiversity and natural resources. They are actively committed to fostering ecological equity and sustainability among all its stakeholders in the shadow of the climate crisis. The training helps them transcend from merely environmentally aware individuals to a strong community which undertakes purposeful and sustained action, equipped with knowledge, skills, and the motivation to make informed and responsible decisions.

Photo credits: Yagnesh Mehta

Why do you believe it is important for children to learn about birds or connect with nature?

When introduced to nature early in life, people often grow up more resilient and content. Immersion in Nature is therapeutic and helps children make real connections with fellow nature-lovers. They gain lived experiences, acquire first-hand knowledge that assists the child to draw conclusions, based on their individual systematic observations and 3600 learning, rather than through memorisation. Nature-based learning sparks curiosity and nurtures the inherent exploratory learning approach of a child, while reducing inhibitions, pre-conceived notions and biases that creep in due to bookish or rote learning. Bird watching and study take these experiences to another level, by developing patience, reducing anxiety, igniting awe, sharp observational (listening and visual) skills, communication, writing, journaling and physical capacities to endure the rigours of long walks, sitting for hours out in the cold or heat, or long travels to and from the birding destinations. Allied skills of birders, such as photography, sketching, checklisting, and time and resource management, assist individuals in weathering the rigours of professional life. Early exposure to birding and nature develops a sense of ownership and compassion, snowballing into activism when their beloved landscapes or species are threatened by degradation or illegal activities.

What tools or resources have helped you in teaching about birds? Can you describe an approach that has worked exceptionally well for you?

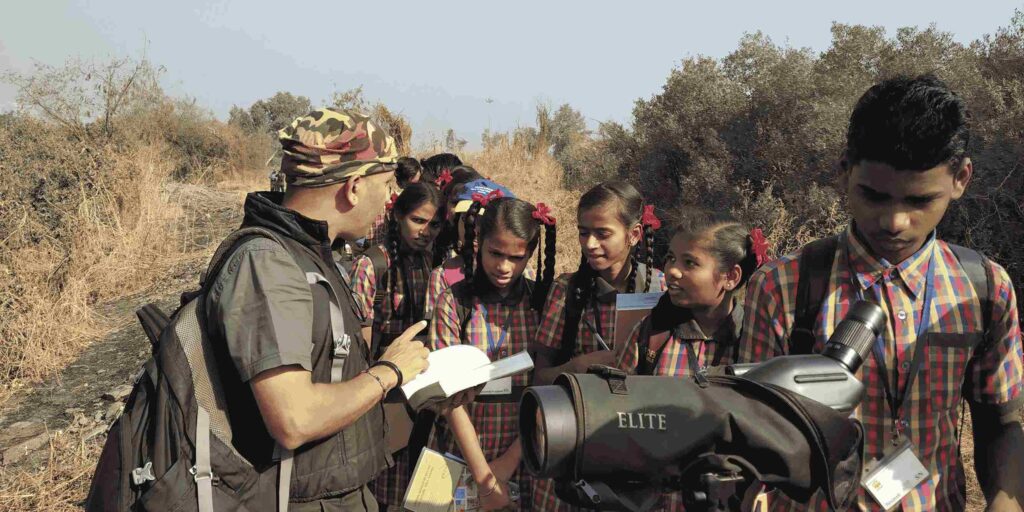

Over the years, I’ve used a variety of tools, resources and techniques to engage amateur naturalists in an engaging, hands-on, and meaningful way. Before each trail, we provide information on the habitat, its ecological features, and a brief history of the site, to help participants understand the characteristics of each ecosystem.

For marine walks, we use field equipment like trays, magnifying glasses, forceps, gloves, guidebooks, and ID charts to safely observe intertidal biodiversity. All collected material is left in the habitat afterwards. Field guidebooks are essential for all walks (birds, insects, or plants) for accurate species identification. Birdwatching trails involve binoculars, spotting scopes, and long lenses to document avian behaviour. During insect walks, we use a ventilated box for safe, close observation before release, promoting curiosity. We also use camera screens to immediately show photos to participants, quickly boosting observational skills.

We encourage using eBird and similar citizen science apps to document sightings. Journaling ecosystems, species, as well as landscapes, has always proven to be an engaging and enriching activity. It enhances deep observation, patience and a scientific rigour even among artists and non-science persons. Interactive games such as crosswords, nature games and puzzles are highly effective tools for indoor and classroom sessions.

Inspired by the effectiveness of the Early Bird “What’s that Bird?” Flashcards, SPROUTS is developing a series of flashcards on different taxa to foster enjoyable, experiential learning about India’s biodiversity.

Photo credits: Rahul Palekar

Have you encountered a significant challenge as a bird/nature educator, how did you overcome it?

The biggest hurdle in nature education is the predominance of English-oriented tools and activities, automatically excluding a large section of society. Additionally, India’s linguistic diversity often makes effective communication difficult with participants who speak only regional languages. I also noticed that many structured nature-based activities tend to cater primarily to urban, financially privileged, and literate audiences, leaving behind those who may be equally curious but lack access. Another major challenge is the lack of dedicated space for nature education within formal school curricula. Often, teachers and parents view nature learning as a distraction from academics, leading to resistance. Moreover, I realised that many of these activities are not inclusive of people with disabilities—such as individuals who are deaf, blind, autistic, or have mobility challenges.

To address these challenges, I consciously adapted my approach: I started switching between languages during sessions and made an effort to learn basic terms in various regional languages, which instantly helped build comfort and trust. To make nature and biodiversity learning more accessible to individuals/groups from all weaker economic backgrounds, I have been conducting sponsored, partnered, subsidised or free birdwatching and nature walks. I collaborated with corporates, NGOs, after-schools, homeschoolers and informal civil society and community-based organisations to encourage nature-based learning. I’ve also envisioned, developed, and taught multiple academic curricula, including an MBA and MSc programme in Environment Management and Biodiversity, respectively, for formal curricular approval. These small adaptations have helped break several barriers, making bird and nature education more approachable, inclusive, and meaningful for a much wider audience.

Do share any memorable moment or experience you have had in teaching kids about birds/nature. Can you recall any insightful instance that shaped your perspective?

My best experiences teaching kids about birds and nature have been with tribal and rural children. For several years, SPROUTS and I curated the Dang Bird and Biodiversity Festivals, hosted by the Gujarat Forest Department. The tribal kids nominated for these camps had immense traditional knowledge. They often changed from being recreational hunters to nature observers.

Another endearing experience was in Odisha, taking a bunch of 45-50 deaf students on bird walks. After gifting their school nature literature and two binoculars, I took them along the Mahanadi (River). Initially, they found it difficult, as I was locating many birds by sound. However, they soon started observing me and quickly began sighting birds themselves. By our third or fourth walk, they were ardent bird-watchers who could identify over 50 species and describe many via sign language. A year and a half later, they remembered me and urged me to take them bird-watching again.

The last experience I would like to share is the one when I led over 100 fifth-grade urban children during a Bird Race, birding exclusively within the city limits. While the adult teams totalled three-digit scores across a 150 km radius, we began collating our own sightings. The children were surprised when our bird count reached 85 species. Regardless of the final tally, all the children forgot the competition and became curious observers who supported one another in sighting more birds.

Have you noticed any changes in your learners after they received exposure to birds and nature-based learning? If yes, what are they? If not, why do you think that is?

Yes, I have noticed meaningful changes in learners after they are introduced to birds and nature-based learning. One of the most evident shifts is in their curiosity and attentiveness. Even participants who initially show little interest gradually become more inquisitive, asking deeper questions about bird behaviour, habitats, and ecological relationships rather than just names. Regular exposure to birdwatching helps them develop sharper observation skills. They start to notice small movements in bushes, subtle changes in soundscapes, or variations in flight patterns that they would have previously overlooked. Their parents reported higher levels of concentration, better retention, larger vocabularies, and improved social skills.

Children who are avid bird-watchers improved their scores in biology and also became better at writing essays or letters, especially if they engaged in field diary writing and journaling. Being outdoors enhanced their physical abilities, immunity, and fitness levels, as well as their sensitivity to the destruction of natural ecosystems such as wetlands, grasslands, forests, and mangroves. Many children voluntarily stopped consuming packaged foods containing multiple layers of plastic. Many young birds were observed to be far more empathetic and responsible than non-bird watchers.

What message would you have for your fellow educators, or somebody starting out in their nature education journey?

My message to fellow educators and newcomers in nature education is straightforward: go beyond names. While identifying species is exciting, the real magic lies in observing their behaviour and interactions, leaving participants with amazing nature stories. This sparks deeper curiosity and connection.

Equally important is engagement with diverse audiences; adapt your communication style, pace, and language to ensure everyone feels included. Ensure your outdoor locations and commute accommodate persons with disabilities (PWDs), utilising multimodal communication. Furthermore, let sessions be collaborative, not one-sided lectures. Healthy competition is acceptable, but the goal should always be collective learning.

Finally, instil ethics and integrity in your participants. Honesty in documenting sightings is far more valuable than inflated numbers. We are not just teaching about nature—we are shaping the attitude with which the next generation will protect it. Parents, educators, and guides should teach with curiosity, compassion, and responsibility.

Anand Pendharkar sir is a bank of amazing knowledge of nature with ability to pass it on to others in a way anyone can understand.